Blog Post by Yari

01/05/2025

Spotify and Apple Music love gamified closure.

But the Yariverse, doesn’t do annualized closure like that, because we are quants.

A year end wrap, a highlight reel that pretends growth is linear, legible, and politely packaged, like you can compress an entire year into five photos with a caption that says “blessed” and a trending audio to get more views.

Some years aren’t meant to be summarized, or even reexperienced.

Some years are meant to be reset, rebalanced, and a New Year can boost your options if you hone in correctly.

Here’s the pretty thesis, in a way any quant from JP Morgan can summarize:

Taking chances is an investing strategy.

In finance, we don’t worship certainty; that would be way too easy. Instead, we price it.

We think in distributions, accept variance, and build portfolios that survive the downside while remaining exposed to upside. The most common mistake most retail investors make isn’t just picking the wrong stock. It’s building a portfolio that feels safe while quietly guaranteeing a small future in return.

And before you quote Warren Buffett to me:

The reality is most might not have the same advantages of investing a small $10 million in a stock and holding it for 15+ years. Warren Buffett had early family access into finance (his dad literally went from stockbroker to U.S. Congressman, which is remarkable insider knowledge across both finance and politics), early business ventures from a supportive family, his first stock investment at age 11, his first real estate investment by age 14, and unlike most homeowners today, the ability to purchase a house for only $31,500 in 1959. Warren also attained a master’s degree from Columbia (love you, Columbia!).

In the simplest terms, Warren Buffett was given more advantages than most, and he was taught how to manage them extremely early on. Still, he only made about 99% of his extreme growth after the age of 50. He became a millionaire somewhere between 30 and 32, but statistically, most millionaires don’t reach that milestone until their 50s, so he was way early. No hate to Warren, the man has an exceptional team and a sharper mind.

For most people, however, the same definition of safety doesn’t apply.

Typically, there’s a quiet cost to safety, a hidden fee you unknowingly subscribe to every month. For most people, safety has seasons, especially in times of mass layoffs. There’s nothing wrong with capital preservation when you genuinely need it, but there’s a version of “safety” that becomes an invisible subscription with negative outcomes:

- If you never buy equities because the market is scary

- Then you only buy defensive names because volatility makes you anxious.

- Then you hold cash for the perfect entry and miss entire regimes.

- You refuse to rebalance because selling winners feels like betrayal.

That’s not risk management. That’s zero allocation to upside dressed up as discipline.

In portfolio terms, sitting in cash is not neutral. It is an active bet that opportunity cost won’t matter. The market punishes that bet slowly, then all at once.

What taking a chance looks like in stocks (not in pretty quotes, but in math)

A chance is simply a decision with asymmetric payoff:

- The downside is bounded (you can size positions, diversify, hedge, or exit).

- The upside is unbounded (compounding has no ceiling in theory).

That’s why taking a chance in markets is rarely about you only live once behavior.

It’s about allocating to optionality: Owning exposure to return drivers that can carry you through a regime shift.

This is why quant teams don’t argue about good stocks; they argue about exposures.

Risk-averse vs. risk-on: two stocks, two futures

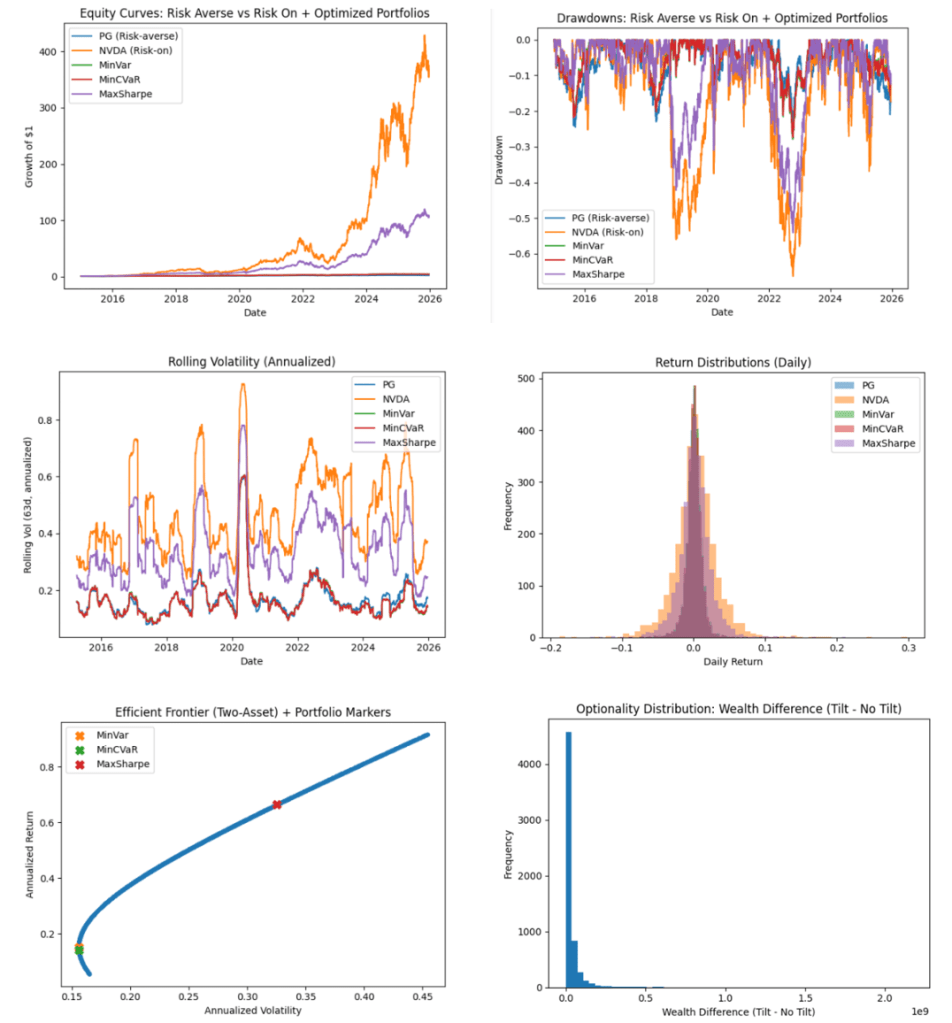

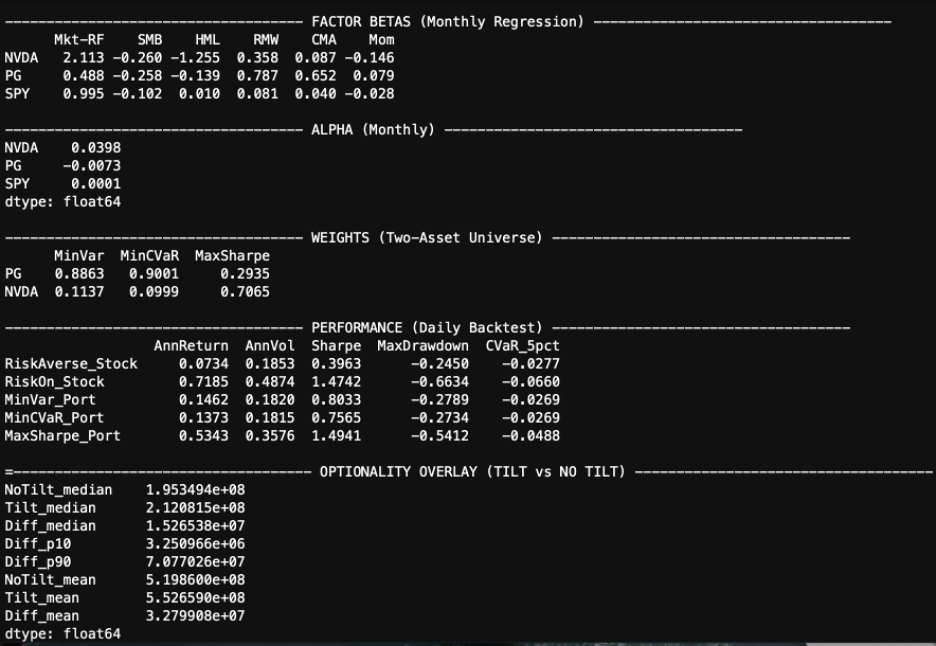

The code explicitly compares two stock “options”:

- Risk-averse stock (ex: PG): historically lower volatility behavior, more defensive cash flow profile, tends to act like a calmer ride than most.

- Risk-on stock (ex: NVDA): higher beta, higher volatility, larger dispersion of outcomes, stronger sensitivity to growth and sentiment regimes.

This isn’t a morality story. It’s a volatility regime decision.

If you allocate only to the risk-averse side, you may experience fewer drawdowns, but you may also cap upside during risk-on markets.

If you allocate only to the risk on side, you may capture outsized upside, but you also accept deeper drawdowns and tail risk.

The answer is not choosing one.

The answer is optimizing a portfolio that matches your objectives and risk constraints.

Why the quant code matters (and why it’s not just a pretty backtest)

The code for this type of portfolio must be quant because it refuses to rely on pure good vibes.

It does four things that separate serious portfolio work from casual chart watching:

- Expected returns are estimated with a factor model

Instead of assuming the past is fate, the model decomposes returns into exposures to persistent risk premia (Fama-French 5 & Momentum) and estimates alpha and betas. - Risk is estimated with shrinkage covariance (think Ledoit-Wolf)

Raw covariance matrices overfit. Shrinkage stabilizes risk estimates, so your optimizer doesn’t hallucinate precision. - Portfolios are optimized under constraints

Long term only, fully invested portfolios:- MinVar: the “risk averse engineer” portfolio

- MinCVaR: the “tail risk guardian” portfolio (focus on the worst case days)

- MaxSharpe: the “rational risk on” portfolio (maximize risk adjusted return)

- Outcomes are judged with real risk metrics

Not just total return. The code computes:- Annualized return & volatility

- Sharpe ratio, & Max drawdown

- CVaR (tail risk proxy)

That’s the entire point of taking chances without messiness. It’s measured exposure.

The New Year as a rebalance, not a recap

A new year isn’t a performance review. It’s about rebalance.

Instead of asking, “What did I accomplish?”

Ask questions that actually change outcomes like:

- Have I over allocated to comfort (cash, low volatility, fear based decisions)?

- Have I under allocated to optionality (momentum, growth, upside convexity)?

- Do my holdings match the future I say I want?

The tragedy isn’t drawdowns. The drawdowns are merely the entry fee.

The real tragedy is building a portfolio so safe it can’t take you anywhere. You might as well put it in a high-yield savings account.

Taking a chance, in markets, is simply this:

Choosing a portfolio that survives the downside and still lets the upside reach you.

And if you do nothing else in the new year, do this one thing with precision:

rebalance into a future that has room to compound.

Here’s a the quick code & visuals (There will be a Part Two on how to interpret it and gain insights from it)

The output should look like this:

The visuals should look like this: